The latest deep dive report by Transformers Foundation, the US-based non-profit representing the denim supply chain, reveals damning evidence that fashion’s chemical certifications are needlessly complicated and woefully ineffective. As the Foundation's Intelligence Director, I’ve been reflecting on the report’s broader implications. For all the fancy chemistry talk of Restricted Substances Lists (RSLs) and Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), my key takeaway from the report is actually very simple: it’s time to let go of certifications – whether chemical, material, or social – as a central pillar of our collective sustainability strategies.

Kim van der Weerd is co-founder and host of Manufactured, a podcast featuring supplier perspectives on sustainable fashion, an Advisor to GIZ FABRIC, and Intelligence Director at Transformers Foundation.

Kim is Intelligence Director at Transformers Foundation, co-founder and host of Manufactured Podcast a podcast featuring supplier perspectives on sustainable fashion. She is also an advisor to GIZ FABRIC. Kim previously worked as General Manager of Pactics Phnom Penh, a garment factory producing for the luxury eyewear industry and as COO of Tonlé, a zero-waste brand that owned and managed its own production – both based in Cambodia. She holds a M.Sc. in human rights from the London School of Economics.

The latest deep dive report by Transformers Foundation, the US-based non-profit representing the denim supply chain, reveals damning evidence that fashion’s chemical certifications are needlessly complicated and woefully ineffective. As the Foundation’s Intelligence Director, I’ve been reflecting on the report’s broader implications. For all the fancy chemistry talk of Restricted Substances Lists (RSLs) and Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), my key takeaway from the report is actually very simple: it’s time to let go of certifications – whether chemical, material, or social – as a central pillar of our collective sustainability strategies.

Certification: the wrong solution for a systemic problem

At their core, audits and certifications are about verifying how an individual entity behaves. Auditors descend upon a company with a standard to uphold and a checklist of things to asses against that standard. Implicitly, then, there is an assumption that unsustainable behaviour is a matter of individual choice. If only we could verify that individuals are making the right choices, our sustainability woes would be solved. In other words: the problem is defined as a matter of intention, of “bad apples” with the wrong values or intentions. The assumption is that certifications keep people on the straight and narrow.

I want to backtrack for a moment. I’m a former garment factory manager. I also studied human rights. I always say to people that as a factory manager I did many of the things my former self, the student of human rights, would have told me not to do. It wasn’t because I’d lost my commitment to the cause, but because I discovered that, in practice, the ethical choices weren’t quite so black and white.

For example, textbooks taught me that subcontracting was bad. But in practice, this wasn’t always so obvious. In one instance I had a very positive relationship with a small family-owned workshop run by a relative of one of my staff. We knew the family well. The strong ties between our two companies meant I could trust them to deliver to a high-quality standard. We were also very familiar with their operations: their space, their machines, and their people. We had an intuitive sense of the volume they could handle, and the lead-times they needed. But they did not have all the documents they would have needed to pass a social compliance audit. They were a small family operation – the administrative burden of being ‘’on the radar’’ would have buried them.

I also had subcontractors that, ethically, I didn’t feel great about working with – but I worked with them anyway. Sometimes this was because they had skills or equipment that we lacked (and we didn’t have enough demand to justify acquiring in-house). Other times, it was because we needed extra production capacity to get an order out on time. I opted to support these businesses because the alternative – at least in the very short term – would have been being unable to pay people on time.

In other words: the reason I engaged in behaviour the sustainable fashion community branded ‘’bad’’ had nothing to do with intention. I didn’t wake up in the morning with a malicious desire to exploit people or the planet. And yet, despite my intentions, I sometimes did things that led to undesirable collective outcomes – both actual and perceived. To a certain extent, factory managers should be accountable for their choices — not all factories are created equal and some do better than others. But in practice, the ethical trade-offs aren’t that simple. Every manager must define a very personal hierarchy of ethical priorities or be paralysed in the face of the mundane day-to-day decisions that collectively form the industry’s social and environmental footprint.

Here’s the thing: as humans, we all do things every day that collectively lead to results that nobody wants. Most of the time, it’s not because we’re bad people who seek to exploit people or the planet, but because the systems in which we operate make it almost impossible to do otherwise.

Certifications: the evidence

The evidence against certifications cuts across sustainable fashion disciplines – from social compliance audits to chemical certifications to material certifications. In the social compliance space, the Global Labor Institute (formerly the New Conversations Project) put forward research1 in 2021 that looked at over 40,000 factory labour audits in more than 12 countries across 12 industries2. The number of violations found in labour audits “was almost unchanged between 2011 and 2018 across all countries and industries.” Meanwhile, the Business and Human Rights Resource Center has an entire portal on “getting beyond social auditing”3. The portal features research on the pitfalls of social auditing and gathers examples of alternatives. Last week, Human Rights Watch published a report4 that details why social audits are ‘’no cure’’ for labour abuses in fashion supply chains (sidenote: Aruna Kashyap, the author of this report will be joining Transformers Foundation for an interdisciplinary panel discussion about how to get beyond audits, on 29th November.)

In the chemical space, our report, “Fashion’s Chemical Certification Complex: Needlessly complicated, woefully ineffective”, written by Alden Wicker, documents how certifications are being leveraged by brands and retailers as market differentiators and as a way to stand out to consumers without having to invest in strong technical expertise in-house. For the denim supply chain, this certification is expensive and time-consuming – diverting resources from much-needed R&D and potentially putting people working in production at risk. On the consumer side, the report cites a current lawsuit brought by American customers against the OEKO-TEX-certified, period-proof panty brand Thinx, “because a university lab found the presence of high amounts of fluorinated chemicals indicating intentionally-added PFAS, when Thinx had promised its customers its [product] was completely non-toxic”. As Alden rightly asks: “how is this happening, while the industry, in some cases, spends millions on testing schemes, auditing, and certifications?”

In the material certification space, Alden Wicker, this time for the New York Times,5 recently documented why “that organic t-shirt may not be as organic as you think.” Despite certifications claiming otherwise and due to pitfalls in the chain of custody processes that support material certification schemes, she lays out why much of the “organic cotton” that makes it to store shelves may not actually be organic at all. Meanwhile, industry insiders seem to agree that most brands and retailers, despite all the certificates, have no idea where their cotton is coming from. For example, Danielle Statham of Sundown Farms and FibreTrace (and also a Founder at Transformers Foundation), recently reflected: “the only truthful way to trace cotton is to have a physical tracer”6. The list of evidence against certification schemes is myriad, and Control Union – one of the world’s largest certifiers of organic cotton – has gone as far as suspending the certification of Indian cotton.7

The evidence against these various types of certification schemes really shouldn’t come as a surprise: if we agree that fashion’s sustainability woes are systemic, then we must also agree that spending our time and money verifying whether individual entities are (or aren’t) making the right choices will also be ineffective. After all, a systemic problem is, by definition, something that no individual can solve alone.

If not certifications, then what?

Effectively addressing a systemic problem requires recognition of two things from all actors involved. First, we all have a role to play, we are all implicated, we are all part of the problem, and we all need to change. We must have the courage to implicate ourselves rather than divert responsibility to someone else. This diversion – as much of the evidence cited above documents – is effectively what today’s sustainability certifications do. Second, we must be open about the fact that our own unsustainable behaviour – however we define that – stems from incentives and systems that we cannot change by ourselves.

Admitting we’re part of the problem whilst also acknowledging that we aren’t able to change our problematic behaviour alone can feel very disempowering; It can feel fatalistic – like we have no choice but to sit back and watch the world self-destruct while flawed certification schemes continue to divert attention and resources. As a garment factory manager, I often found myself feeling utterly overwhelmed trying to abide by all the ethical rules that brands’ sustainability team members expected me to abide by on the one hand, and the complexity and nuance of my lived experiences on the other. But in the end, the litmus test to which I held myself was basic: did any of my actions create an incentive for unethical behaviour? If my business partners were ever discovered to be engaging in unethical behaviour, could I look myself in the mirror and confidently assert that nothing we’d done had encouraged, motivated, or contributed to their decision to behave that way?

For example, as a factory manager, I led our SA8000 certification. As part of that certification, I was responsible for demonstrating that our suppliers were abiding by certain social standards. I did this, in part, by collecting commitment statements from those suppliers. I knew these pieces of paper meant little, and so did our auditors – and yet I needed them to get the certification. Instead, I wish auditors had asked me about things that were within our control. For example, had we proposed design changes to the brands with which we worked, to reduce the need for subcontracting? Had we considered buying equipment in-house instead of subcontracting? And if not, could we demonstrate that we didn’t have enough volume to justify it? Were we actively seeking out new customers, brands, that prioritised sustainability? Even more importantly, how had we treated our suppliers? I wish auditors had asked to see evidence of whether we paid our suppliers on time. I wish auditors had asked whether we paid our suppliers’ deposits. I wish auditors had asked to see evidence of how we communicated with our suppliers: how and when did we give them forecasts? What did we do when those forecasts were wrong?

Because the truth is: I could have done better. Having an auditor push me to think through what was within my control (and likely to impact the choices made elsewhere in the supply chain) instead of focusing on leverage, outward-oriented assessments, and verification would have made us a more responsible business. Solving systemic problems requires us all – from brand, to apparel manufacturer, to chemical company, to farmer and beyond – to hold up a mirror and ask ourselves a very simple question: how does my behaviour impact you? Walking the talk should mean inviting auditors in to assess how our own behaviour impacts the world around us in order to make sustainable headway, rather than seeking to find fault with someone else’s behaviour.

To learn more about chemical certification pitfalls and the parallels with social and material certification schemes, join Transformers Foundation for an interdisciplinary panel discussion on 29th November at 3PM CET. The discussion convenes experts across fields and asks how the industry can move beyond certifications.

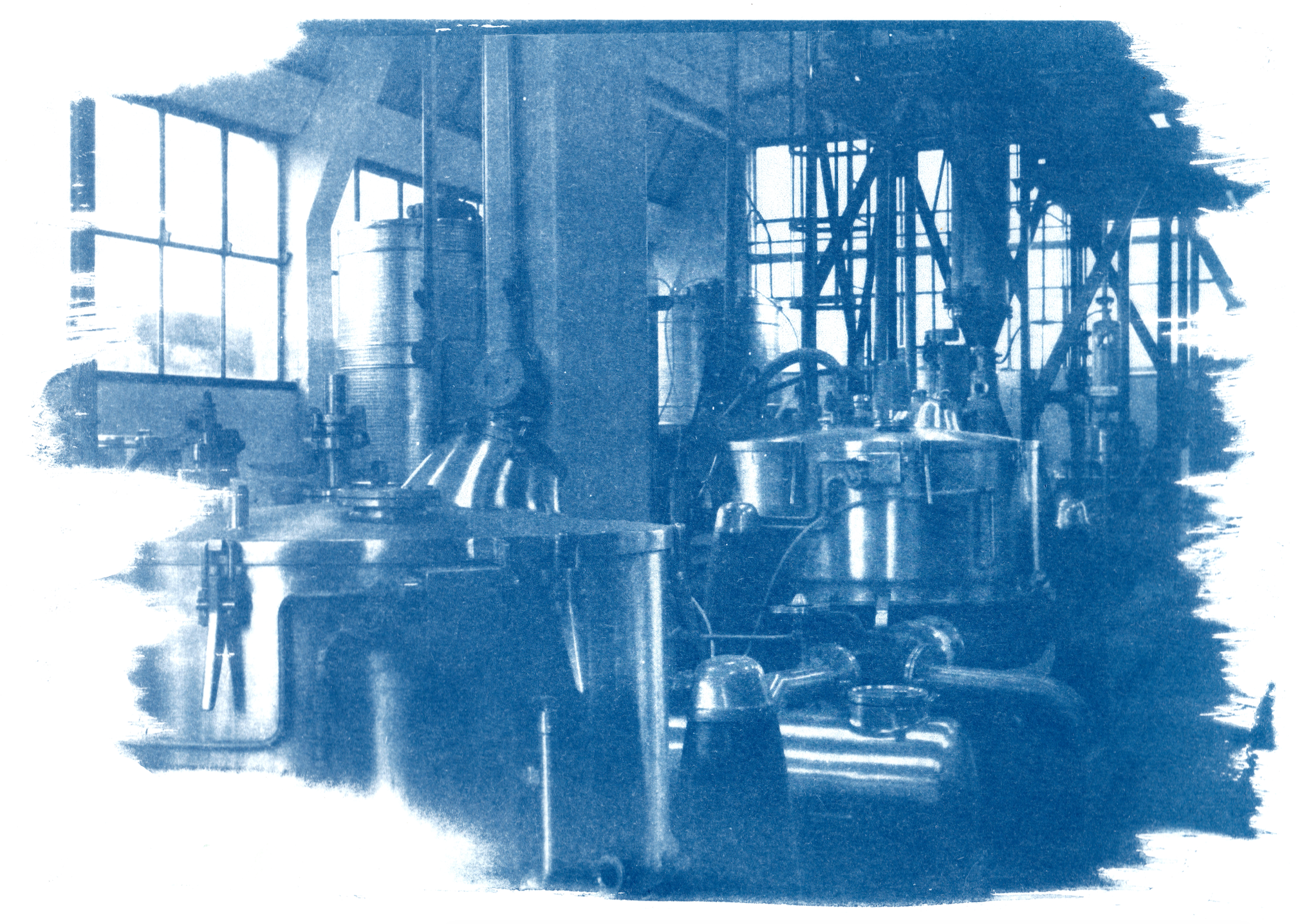

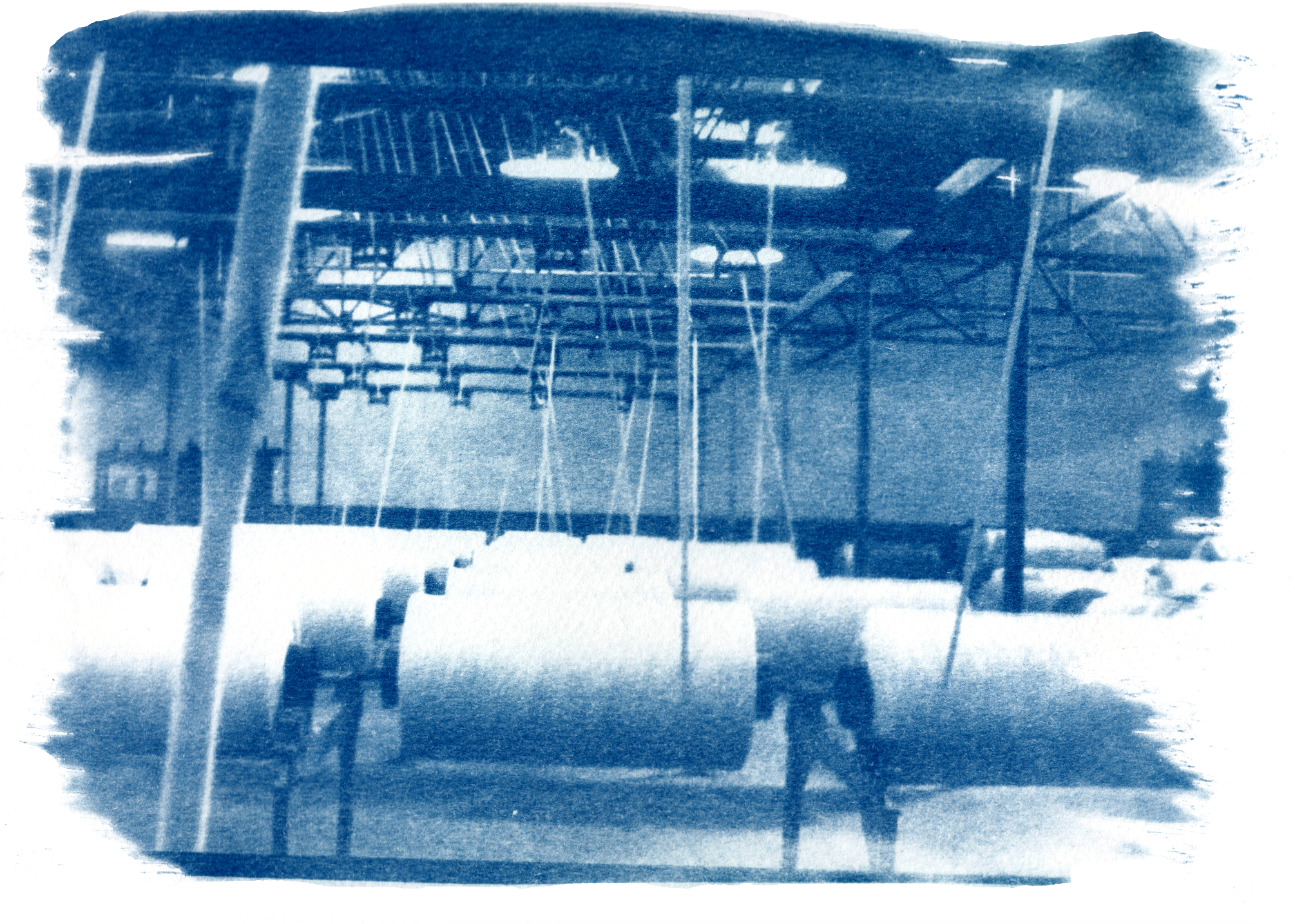

Images courtesy of Heather Knight

*The opinions expressed in this OpEd are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Techstyler.

OUR GIFT TO YOU!

Throughout December, save 25% on your Techstyler membership.

Add GIFT25 at checkout.

- 1 Sourcing Journal, Does Private Labor Regulation Work? Probably Not (1 December 2020)

- 2 Private Regulation of Labor Standards in Global Supply Chains

- 3 Business & Human Rights Resource Centre

- 4 Human Rights Watch, Social Audits No Cure for Retail Supply Chain Labor Abuse

- 5 New York Times, That Organic Cotton T-Shirt May Not Be as Organic as You Think (13 February 2022)

- 6 Fibre2Fashion, Interview with Danielle Statham

- 7 EcoTextile News, Control Union to suspend certification of Indian organic cotton (14 April 2022)